Most contractors are well aware that Texas law provides for mechanic’s liens under Chapter 53 of the Texas Property Code, also known as “statutory liens.” As most are also aware, the statutory lien process is complex and has a slew of notice requirements with stringent deadlines which, if not met, can be fatal to perfecting a lien claim. This is the second part in a series on the statutory lien process from soup-to-nuts – read Part 1 – Gathering Information here.

Part 2: Preserving Your Constitutional Lien Rights

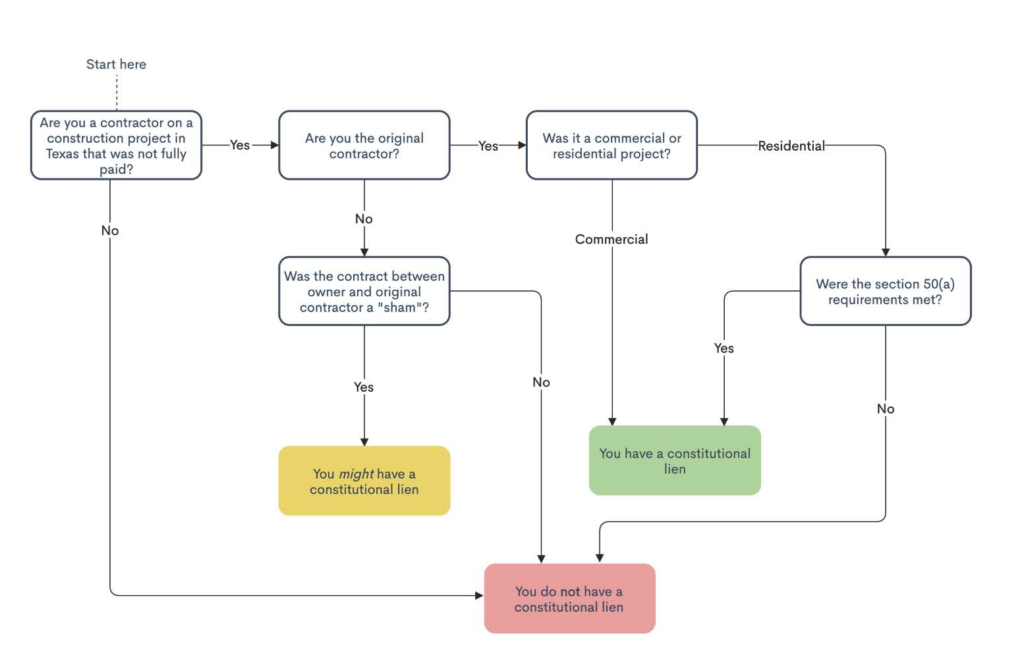

In addition to the statutory lien, the Texas Constitution provides another mechanism for a mechanic’s lien that is available to Texas contractors, aptly called the constitutional lien. Constitutional liens, unlike statutory liens, are automatic in that they are self-executing. Critically, depending on your status (i.e., are you an original contractor or a subcontractor?) and the type of project (i.e., residential or non-residential), the requirements for a constitutional lien change and affect whether a constitutional lien has self-executed (or whether it is even available).

Once you have determined that a constitutional lien exists, you are back in statutory lien territory. That is, you should (it is not required but I will tell you that you must) file a lien affidavit and file an action to foreclose on your lien and collect what is owed to you. On the other side, if you are a homeowner and a constitutional lien affidavit has been filed on your residence, you should verify that the requirements for a constitutional lien were met and, if it they weren’t, file an action to remove it as soon as possible.

When Does a Constitutional Lien Exist?

Section 37 of Article 16 of the Texas Constitution provides:

“Mechanics, artisans, and material men, of every class, shall have a lien upon the buildings and articles made or repaired by them for the value of their labor done thereon, or material furnished therefor, and the Legislature shall provide by law for the speedy and efficient enforcement of said liens.”

Let’s break that down.

First, you must be an original contractor that improved a building or article. This first requirement is generally satisfied if you performed some work on or your materials were utilized within or on the project or property. It becomes nuanced when you provide materials or improve only a particular aspect, i.e., repairing the air conditioning unit. Only the original contractor, i.e., a contractor that contracts directly with the owner, is entitled to a constitutional lien. If you are a subcontractor, like a plumber or electrician, you are unlikely to have a direct contract with the owner and are therefore are ineligible for a constitutional lien. But hold on! There is an exception and it is addressed below.

Second, the constitutional lien is self-executing – which means that the original contractor need not send any notice to the owner for a mechanic’s lien to exist, though it is recommended. To properly assert a constitutional lien, you must file a lien affidavit—like you would with a statutory mechanic’s lien. Filing the lien affidavit will attach the constitutional lien to the property and transfer it if it is sold to a bona fide purchaser by the owner.

To summarize, if you are an original contractor, i.e., a contractor with a contract with the owner, who improved a non-residential building or article that has not been paid in full for your work, you have a constitutional lien on the project and can file an action to foreclose on it.

Do Constitutional Liens Exist on Residential Projects?

The short answer is “yes.”

The long answer is that many requirements must be met before a constitutional lien will self-execute on a project where the original contractor has not been paid. If you are a homeowner and a constitutional lien has been filed against your property, read on to see whether all the requirements have been met. If not, then the constitutional lien has been improperly filed.

Requirements for a Residential Constitutional Lien

Section 50(a) of Article 16 of the Texas Constitution sets out the requirements that must be met to trigger a constitutional lien.

- The original contractor has a written contract with owner that is signed by both spouses (if owner is married);

- The contract must be executed at least 5 days after the owner applies for an extension of credit for the work and material (unless the work and material is for immediate repairs that affect health and safety of the residents and the residents confirm the same in writing);

- The contract for work and material provides that the owner can rescind the contract without penalty or charge within 3 days after the contract is executed (unless the work and material is for immediate repairs, like no. 2); and,

- The contract for work and material is executed by the owner and owner’s spouse only at the office of:

- A third-party lender making an extension of credit for the work and materials;

- An attorney; or,

- A title company.

As you can see, the fourth requirement is a challenging one. If you’re a homeowner and not all of the above requirements have been met, you are entitled to file a motion to file a motion to remove invalid or unenforceable lien (similar to method provided for under section 53.160 of the Texas Property Code). Likewise, if you’re an original contractor and not all of the above were met when the contract was signed, you are unable to assert a constitutional lien.

What if I am Not the Original Contractor?

The policy behind the constitutional lien is that the owner already knows that you, the original contractor, were not paid because they have a contract with you. That knowledge does not exist if the owner does not have a contract with you. For example, if you are a subcontractor that contracted with the original contractor and the original contractor fails to pay, you cannot file a constitutional lien because it cannot be presumed that the owner knows you were not paid.

However, under the Property Code, a subcontractor can become an original contractor if the contract between the owner and the original contractor with whom the subcontractor contracted is a sham contract. If a sham contract exists, the subcontractor will be considered to be in a direct contractual relationship with the owner—becoming an original contractor—and have lien rights as an original contractor.

To prove a sham contract, the subcontractor must show at least one of the following (and because it’s wrought with legalese, I include examples):

- The owner contracted with the other person for construction or repair and the owner can effectively control that person through ownership of voting stock, interlocking directorship, or otherwise;

For example, ABC, Inc. is the owner of a project and it contracts with XYZ, LLC to construct a commercial building. XYZ, LLC subcontracts with John Plumber, LLC. XYZ, LLC is the original contractor and therefore has constitutional lien rights if it is not paid. John Plumber, LLC as the subcontractor does not. However, if it is found that ABC, Inc. owns and can control XYZ, LLC, i.e., XYZ, LLC is a subsidiary of ABC, Inc. (think Alphabet and Google), then John Plumber, LLC could be considered to be in a direct contractual relationship with ABC, Inc. and have constitutional lien rights as an original contractor.

- The owner contracted with the other person for the construction or repair of a house, building, or improvements and that other person can effectively control the owner through ownership of voting stock, interlocking directorships, or otherwise;

This is similar to the preceding example but instead of the owner controlling the contractor, it is the other way around. In this case, XYZ, LLC has the ability to control ABC, Inc.

- The owner contracted with the other person for the construction or repair of a house, building, or improvements and the contract was made without good faith intention of the parties that the other person was to perform the contract.

For example, John Doe is the owner of a project and he contracts with his friend, Kon Tractor, to remodel his convenience store. Behind the scenes, though, John is going to have a big hand in hiring subcontractors, suppliers, etc. and only hired Kon because John wanted to funnel some funds to Kon because Kon is having money troubles.

Most important, even if you have a constitutional lien you must file a constitutional lien affidavit. Otherwise, the only people that know you have a constitutional lien are yourself and the owner, and if the owner sells the property the project sits on, you have lost your constitutional lien! Fortunately, the filing process mirrors that under the Property Code.

*Rishabh Agny is a civil and commercial litigator, focusing on construction law, at the Chapman Firm, PLLC, in Austin, Texas.